This article is part of a series of publications in which stormwater experts from different cities share their cities’ journey in nature-based solutions for stormwater management. The City Blues project has come up with a transition scale which is used as a guideline to help cities describe and measure their progress in implementing nature-based solutions. The scale and descriptions of its stages can be found on the City Blues webpage: D1.3 Critical KPIs for the joint operational model design process.

How did the city become interested in nature-based solutions?

The first nature-based stormwater solutions in Malmö, Sweden started in the early 1990s. At the time, they were not called “NBS,” but looking back, that is exactly what they were. It all began with one person in the technical department who was really passionate and recognized the potential of stormwater as a resource rather than a problem to be hidden underground.

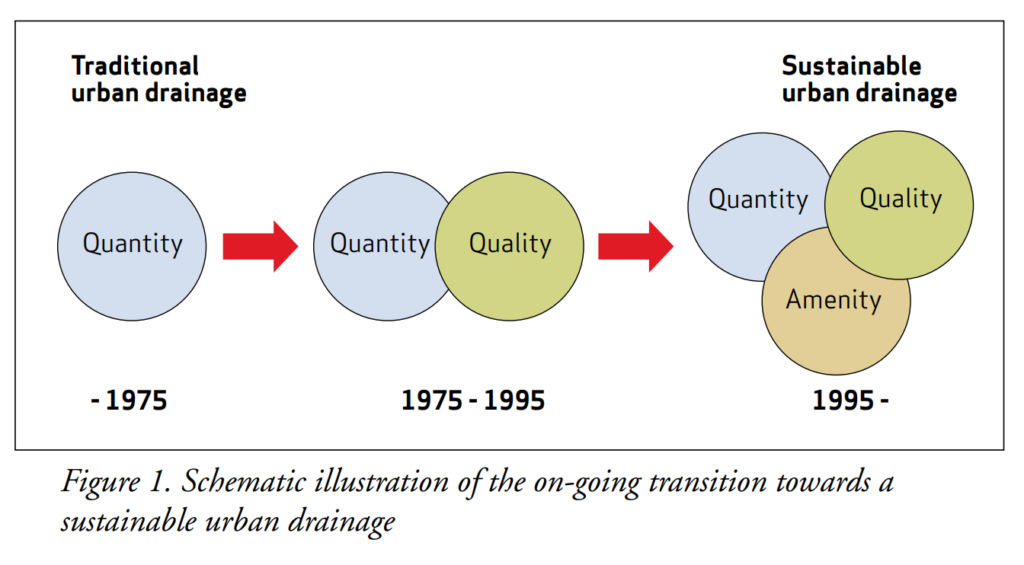

Back then, the thinking was shifting. In the 70s, the focus was purely on quantity – removing water as quickly as possible. Later, quality became a focus, and in the 90s, Malmö started looking at the added values water could bring. These added values included recreational opportunities, biodiversity, and social benefits. A few people from different departments got together and just started building things. It worked, and that is how it all began. Now stormwater management is always part of urban planning and building new urban areas.

What are the main benefits of NBS in the city?

The main idea of NBS is to bring nature back into the city. When doing that, we get all the ecosystem services that come with it – like better water management, more biodiversity, and spaces that people actually enjoy being in.

It is not just about handling stormwater. These solutions make the city more liveable. People get green spaces, trees, flowers, and even open water features right outside their homes. Plus, it helps reduce the pressure of the whole sewer system, especially during heavy rains.

On what transition stage would you rate the work of the city?

Malmö can be seen at the upper end of the stages. Of course there is the want to reach the full potential, but we still have the old city centre where infrastructure and land use were not originally designed with NBS in mind. Therefore, it is not as easy to adapt retrospectively. But when planning for new areas, Malmö’s work is probably in the top level because then stormwater management is included in the planning from the start. We have also very strong political support and sufficient funding for the solutions.

What are the main challenges for nature-based solutions?

Space is definitely the biggest challenge, especially in the existing city. There are a lot of things that need to fit into a small city. The planning is done on a long term. When planning strategic spots for NBS in the future, potential areas are hard to find because it is so crowded – there are buildings, roads, bike lanes, parking, and all kinds of infrastructure that also needs space. Even underground, where there is the possibility to store water, is packed with pipes and cables.

Cost is another issue. These solutions are not cheap, and planning needs to be done carefully to make them happen. Legislation can also be tricky. We are only working on public land, and the city only owns about 30% of the total land area. That limits what is possible to do. And when there are areas with lots of different property owners, it is really hard to get everyone on board. If there is just one owner, like a municipal housing company, it is much easier.

How do you engage stakeholders in NBS work?

When working on public land, we do not always have to do big hearings – unless it is a new development area, then it is required by law. In existing areas, feedback is sometimes asked as a courtesy. But honestly, there are not that many alternatives to the solutions that we can do because the space is so limited. Therefore, it is challenging to involve stakeholders in the planning phases.

The city’s bigger focus now is trying to get private property owners do different solutions themselves and to support them and provide information. Malmö is building networks with the property owners and there will be a conference this fall to improve dialogue. We are testing different methods and still figuring out what is the best way to reach out – what kind of support people need, what motivates them. Some will probably ask for funding or help with permits. Understanding how to reach different types of owners in the future, from big property companies to individual households is important.

What are some aspects that could be further developed?

It rains heavily in Malmö from time to time. The sewerage pipes and pumps are not enough by far. The city is very flat as well so the water cannot be guided or infiltrated fast enough. It is a large problem that the city faces. We need to figure out how does the water flow and where can it can be steered so that it does not damage any point in the critical infrastructure, for example. City of Malmö does not have stormwater fee, either, so all of this is done with tax money or other types of funding.

What advice would you give to other cities?

Start with new areas. It is so much easier when you can plan nature-based solutions from the beginning. If thinking about stormwater early – where it goes, how it can be used – it is possible to design spaces that work well and bring added value.

Also, start small. Try a pilot project. That way, cities can learn how things work, how different departments and utility company need to communicate and collaborate, and what kind of challenges come up. Once that is done, it is easier to scale up. It is all about building experience and figuring out how to make it work in cities’ own context.